Early Work, 1968-1984

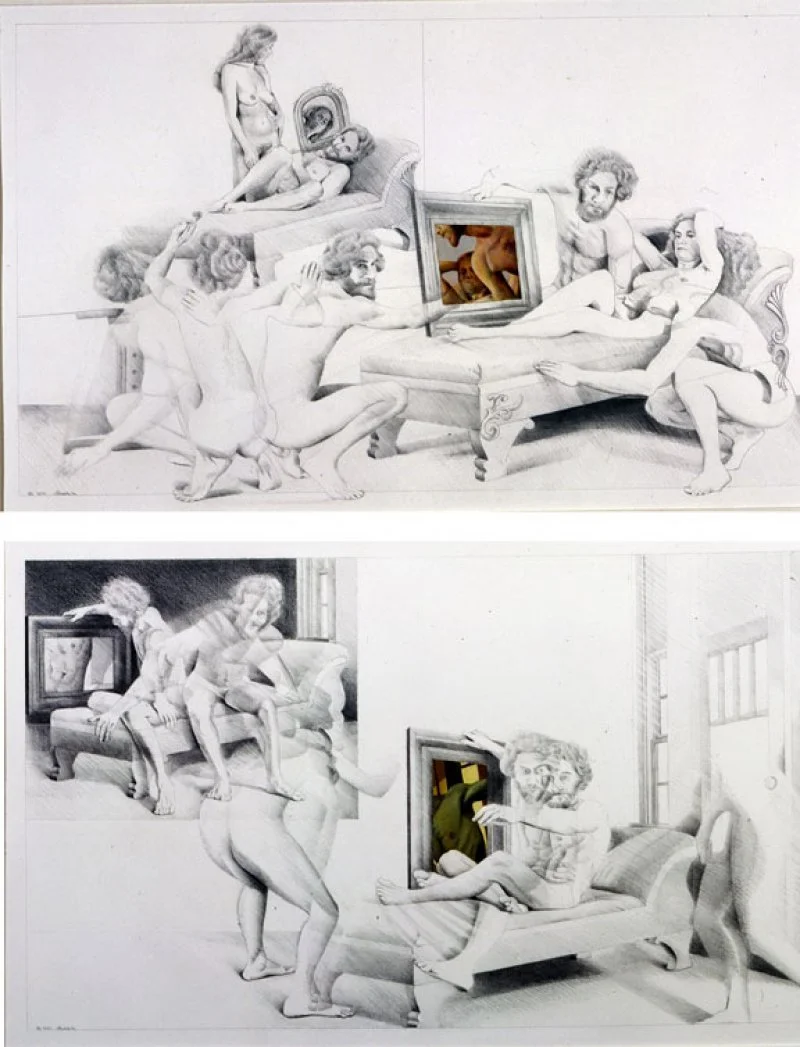

Through the Looking Glass, 1983, 43" x 67", oil and graphite on paper

Genesis, 1983, 44" x 72", oil and graphite on paper

Rape of Europa, 1984, 44" x 64", oil and graphite on paper

Battle Between Centaurs and Lapiths, 1983, 44" x 67", oil and graphite.

Mirror, Mirror, 1983, 43" x 67", oil and graphite on paper

Creation, Temptation, Expulsion, 1976, 21" x 36",cast paper, oil and gr...

Genesis Series, 1978, 21" x 36", cast paper, oil and graphite on paper

Artist in the Studio, Rocker Series, 1983, 43" x 67", oil and graphite...

Voyeur, 1980, 47" x 36", oil and graphite on paper

Marty and Me, 1979, 22" x 30", mixed media on paper

Self Portrait, 1980, 47" x 36" , oil and graphite on paper

Chef d'Orchestre, 1980, 47" x 36", oil and graphite on paper

Up Front, 1980, 47" x 36", oil and graphite on pape

Andrei, 1984, 3 panels, center 40" x 44" left and right panels are each 40" x 22 1/4", graphite and acrylic on paper

THE WORK of MURRAY ZIMILES

With all the intricate interplay and furious energy of multiple figure sequences, it is the space in Murray Zimiles’ work that initially fascinates. It is not a nothing space, made by absence, but the simplest and most elegant of something spaces, created by an almost invisible horizontal line extending from one side of the drawn frame to the other. With one stroke a whole world is created, a world of potentiality and opposition – between depth and plane, earth and sky, substance and spirit. In terms of Zimiles’ major themes, it is a paradisiacal space which, in fact, miraculously coincides with the word “paradise” in its derivation from the Iranian for “enclosed park” and the Greek for “surrounding wall.”

And the realm Zimiles introduces to us is indeed paradise, or at least the condition of paradise, directly in the “Genesis” series and less directly in the artist and studio series. The one describes a paradise lost, the other a paradise partially, or intermittently regained. The space makes one remember the connection between the two, that one is the extension of the other, or perhaps it’s opposite, its earthly side. The same line continues from one realm into the other, although in the “Genesis” it signifies a meeting of earth and void, or void and void, and in the studios of floor and wall.

That is the stable, not to say eternal part of Zimiles’ work, based not on the perspectival construction of Renaissance space – although it is at times suggested – but on a thoroughly modern conjunction of planes, which create an enclosed field of space. Because it is a field and neither a predetermined structure nor a realistic, it can accommodate a great diversity of phenomena and effects namely the different styles, from impressionistic to realistic, in which pictures and other images are painted, and the varying techniques of drawing used to indicate movement and resolution in the endless energized dance of multiplied figures. The figural sequences are again reminiscent of Renaissance or Baroque figure groupings, but only reminiscent. Their configuration is dependent on a cinematic connectedness, a line of movement that is also random, not a hierarchical set of relationships. These general references to past art, and other more specific ones, play an interesting role in Zimiles’ work in that they do not plead a special case for a particular approach but are rather transformed and become part of, in the artist’s words, “a multi-layered art in which formal and pictorial elements build upon the past, overlap, suggest, allude, interpret, amuse, and are synthesized into my own vision of art and life.”

Vision, or wholeness, is something that exists only in multiplicity, and the artist himself is its synthesizer. The “Genesis” scenes which include the Expulsion, or a fall from grace, describe a loss of integration in the whole, a splitting apart, essentially into man and woman. The globe and eagle, images of unity and absolute primordial power, themselves become agents of division, the see that splits the void.

The artist and studio series represents a reintegration through the relationship of the artist to his work. But it is a process full of deception and ambiguity, in which the artist is seen in an extended self-portrait, appearing and disappearing in an interconnected spiral of stationary contemplation and blurred motion. He paints pictures in a wide range of styles and techniques – of landscapes, of the eagle, of himself – none of which are finished, none of which express all that he has to express, but all of which recreate some aspects of the whole. His own figure moves through the space like an abstract force in a constant state of becoming, sometimes absorbed into the brushstrokes and formal configurations of the paintings he is working on, an experience Zimiles has described as becoming “one with the paper.” The artist, in other words, is both within the picture and in reality focused completely on his art, which in itself is a reintegration and reinstatement of unity and wholeness. But this also occurs thematically. Particularly when images from the “Genesis” are transferred to the artist and studio, a kind of reversal of the Genesis takes place. A striking example is the one in which the artist, while painting a picture of the eagle in flight is suddenly confronted on a clear vertical axis at the very center of the picture with the powerful form of the eagle realistically painted above and in front of him. The figure of the artist at this point, crouching in an attitude of amazement, is modeled in cast paper and therefore frozen in the moment of recognition. The eerie conclusion of this union occurs in the area where the shadows of eagle and artist join, one cast by a three-dimensional figure he other by an illusion.

The atavistic power of this image characterizes much of Zimiles’ work, though it usually is expressed in a less stark and elemental way. It is the deepest layer of his art, the one that pushes closest to the source of creation.

Donald Goddard - 1978